Human rights are meaningless as long as Nature is rightless

Rights of Nature as a positive tipping point

When the parties of the UN Climate Convention met for its 28th Conference (COP28) in Dubai in November, the urgency was palpable. Demand for energy as well as greenhouse gas emissions have reached historic levels after the pandemic, despite decades of climate conferences. The ecological crisis is far more serious than most people realize, according to over 200 scientists behind the 'Global Tipping Points Report' presented at COP28. Irreversible tipping points which pose incalculable risks to humanity in terms of migration, political instability and economic collapse are looming. Even with current warming, the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets could collapse, coral reefs die off and permafrost in the northern hemisphere could thaw (further accelerating climate change). The cold autumn in northern Europe is what would be expected from the breakdown of AMOC - the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. There is no way of knowing if this is the case. We are now in unknown territory, we can make more or less informed guesses, but they are still guesses. Rapid, non-linear changes have so far been poorly understood and their consequences are inherently difficult to predict.

The 75th birthday of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights coincided with COP28. How do we talk about human rights when the living systems we are completely dependent on are collapsing? It seems easy to forget, but basic human needs of food, water and energy are covered by soil, lakes, mountains, oceans and forests. When ecosystems are degraded, the poorest people suffer the most. When nature is no longer able to deliver as before, conflicts and wars follow, causing further environmental degradation and violation of human rights. These links were recognised when the UN General Assembly last year adopted a resolution recognising a clean, healthy and sustainable environment as a human right, something that 80% of member states already had in their legislation. How are we to deal with the gap between this understanding and the apparent inability to avoid an ecological crisis of a magnitude never before experienced by humanity?

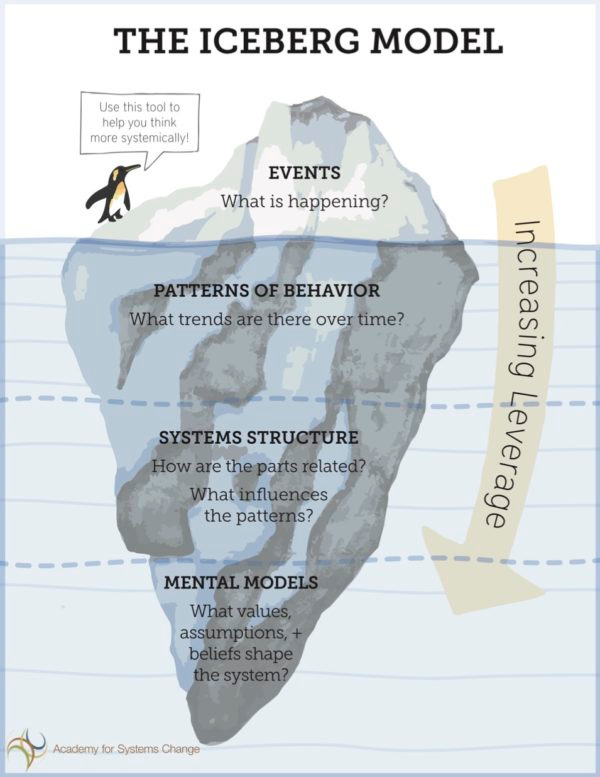

The final agreement from COP28 calls on governments to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems”. This effectively means that the great acceleration - the time of exponential resource use after World War II - is over. Needless to say, this is not acknowledged by the parties to the agreement. (I´ll write a separate piece on what this may mean). The great acceleration, interestingly, coincides neatly with the lifespan of the Declaration of Human Rights. How will the conditions for human development change by its ending? According to the report on tipping points, the only thing that can help us avoid dangerous tipping points in ecosystems is positive tipping points in society. Social changes that lead to shifts in how we collectively behave. The report calls for a systems-thinking approach. However, the examples given of promising positive tipping points, for example cheaper solar power, cheaper electric vehicles, green ammonia in fertilizer, does not reflect such an approach. Proposing these change-of-fuel measures in the light of severe threats to the planet´s life-supporting systems seems outright silly. Their qualities are nowhere near the transformative level required.

Systems thinker Donella Meadows (lead author of the Limits to Growth study, published for the very first UN environmental conference in 1972) investigated 'leverage points' for systemic change. According to her, powerful leverage points have to do with cultural and existential changes. Effective leverage points require shifts in what we believe is important, collectively strive for and the rules we set, or even how we perceive the world and our place in it. Superficial phenomena such as new technology or individual behavioral changes lack the necessary power.

In Western society, we cherish the belief that the world revolves around human beings. The Christian God created us in his image and endowed us, and no one else, with a soul. During the Enlightenment, science gradually took over the role of the Church as interpreter of the world. Francis Bacon, the 'father of modern science', argued that the mission of science was to control and dominate the universe for the benefit of humanity. This anthropocentric notion is still alive and kicking, visible in terms such as 'natural resources' and 'ecosystem services'. Nature exists for the sake of humans, as object and property. We may consider protecting it to the extent it benefits us. It is this worldview that enables us to perceive economic growth as a shared goal. Based on the idea that the only existing needs are human needs, we can tell ourselves that over-fishing the oceans, cutting down the forests and opening new coal mines means growth, despite the knowledge that it leads to devastation. As long as there are no other needs and interests to consider, we will continue to liquidate ecosystems, now on an entirely new scale: Norway, for example, is currently preparing for deep-sea mining. Not even the planet is enough anymore; Nasa is organizing an expedition to the moon to look for minerals. (That a woman and a person of colour will for the first time participate in the extraction of space resources offers little comfort).

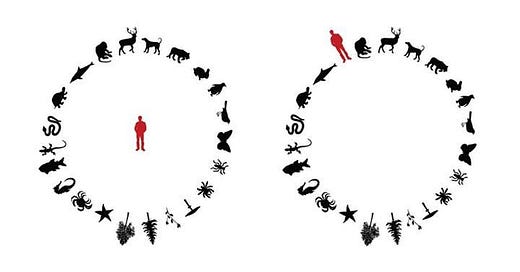

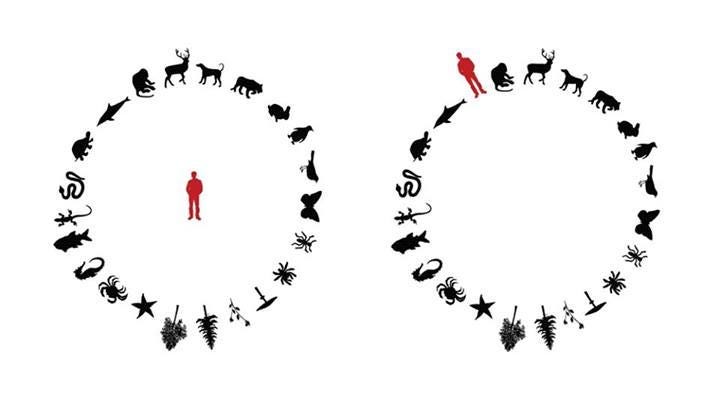

This narcissistic worldview is based on a misunderstanding, according to cultural historian Thomas Berry. The universe wasn't created in order to please humans. It is not a collection of objects but a community of subjects. Berry was one of the first to articulate the idea that not only humans, but all living things have rights. This means that the world is not a pantry and garbage dump for us to control and manage to the extent that it favors human interests, not an 'environment' but a living whole that we participate in. We need to extend our sphere of interest to include the needs and interests of more-than-human beings. Human rights are a subset of nature's rights, according to Berry.

To those stressed about global tipping points with civilisation-wrecking consequences, this may seem esoteric, but it is not. Rights of nature is a powerful leverage point that simultaneously challenges the dominant worldview and rewrites the rules of society. For the legal system, it is no more remarkable that forests, rivers and oceans are legal subjects than that corporations are. In Panama, the rights of nature were recognised in law in 2022, explicitly acknowledging the close relationship between the rights of nature and the beliefs of Indigenous peoples. In November of 2023, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled the Cobré Panamá copper mine unconstitutional. The court reaffirmed that nature is a subject of rights – including the right to be protected, restored, and to regenerate its life cycles – and ruled that the contract with a Canadian mining company did not meet these standards because it failed to include strict measures to prevent environmental damage. One of the world's largest copper mines, accounting for no less than 75% of Panama's export revenues, will now have to close.

These are the kind of uncomfortable decisions that need to be made if we are to avoid catastrophic ecological tipping points. Whether we like it or not, we find ourselves in a predicament. Either we use the uniquely human ability to imagine a different way of life and choose it, or we wait for the Earth to tip us into something far more uncomfortable. The recognition that humans are not the center of the Earth is a social tipping point with massive potential, perhaps a shift in understanding of the same magnitude as when Galileo suggested that the Earth is not the center of the universe. It is definitely a similar adjustment towards a more true perception of our place in the world.

To correct this cultural misconception is also to regain our human dignity, writes Thomas Berry: "The natural world is the larger sacred community to which we belong. To be alienated from this community is to become destitute in all that makes us human. To damage this community is to diminish our own existence." As long as nature lacks rights, it will ultimately be impossible to maintain human rights. When we change the rules of society to recognise the relationships between humans and more-than-human beings, we can begin to co-exist in a healthier way. It will be a new chapter in the story of humanity.

Thank you Pella. I got to meet Donella Meadows briefly before she died. I was a freshman in college, just beginning to comprehend the state of our relations to the rest of life. Blessings to you. -Adam

Watch this lovely peek into the process in Panama!

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/legislation-giving-nature-the-same-rights-as-humans-gains-ground-in-some-countries/