On the need for an Embassy of the Baltic Sea

- why "keeping the seas stocked" is an impossible idea

As I write, representatives of 196 states are in Cali, Colombia for the 16th meeting of the Convention on Biological Diversity, COP16. The theme is Peace with Nature. The meeting is a follow-up on the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework - equivalent of a Paris Agreement for nature - agreed in 2022*. As the participants cheered the ambitious goals of this historic framework, they committed to deliver national strategies for how they would reach those. Only 10 % have done so (Sweden is not one of them).

When swedish parliamentarian Rebecka Le Moine asked Prime minister Ulf Kristersson about how Sweden plans to reach the goals it has committed to - explicitly asking him to not respond by stating that their opinions differ - he responded… that their opinions differ. But in this case, differing opinions are not interesting. There is a political responsibility that needs to be taken. How are we to understand this gap between scientific knowledge about the state of biodiversity and what needs to be done, and the political will to act in response?

The same day as the start of COP16, the EU Council began negotiations on fishing quotas for the Baltic Sea. The cod populations have collapsed. Despite researchers’ warnings that herring populations are heading in the same direction, the ministers decided to more than DOUBLE the fishing quota for herring. István Nagy, Hungarian Minister for Agriculture and chair of the session, commented on the decision: “with today's agreement we aim to strike a balance between helping fish stocks recover, protecting marine ecosystems, and ensuring the viability of the sector in the future”.

The Baltic Sea is one of the most polluted bodies of water on Earth and has been described as close to ecosystem failure. The causes are very well known. Despite all the good intentions, legislation and communication, the goal to keep viable fish populations is failing miserably. And for what? Fish are being harvested by large-scale industrial trawlers; with the 20 largest boats accounting for 95 per cent of the catch in 2021 (mostly herring and sprat). The herring is not even eaten by humans, but is a protein source for salmon, chickens and mink; of the herring landed in 2021, only 10 per cent went to human consumption.

It is as if we are at war with nature, and as UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said towards COP15, this war is suicidal. International frameworks like IPBES, IPCC and CBD are therefore increasingly calling for transformational change of societies, i. e. “fundamental, system-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values”. Professor in Energy and Climate Change Kevin Anderson expresses it as “there are now no non-radical futures. The choice is between immediate and profound social change or waiting a little longer for chaotic and violent social change.”

So how do you bring about transformation?

Radical means “coming from the root”. I believe we have to understand that at the root of our western culture is the assumption of nature as object, of control and domination of what we call “natural resources”. Unless we change that, we will not be able to live in peace with nature, no matter how bold the goals of our agreements. (I even hesitate to use the word “nature” here, as it is a product of this othering of the living world beyond humans). This assumption is so old and so deep that it is difficult to spot. I was teaching master students at Uppsala university recently. One of them began a question by saying: “Most development projects are destructive”. It was so striking that I wrote it on the whiteboard. It is a strange thing, living in a society where we agree that such a statement is true. What then, do we mean by development? What do we mean by sustainable development?

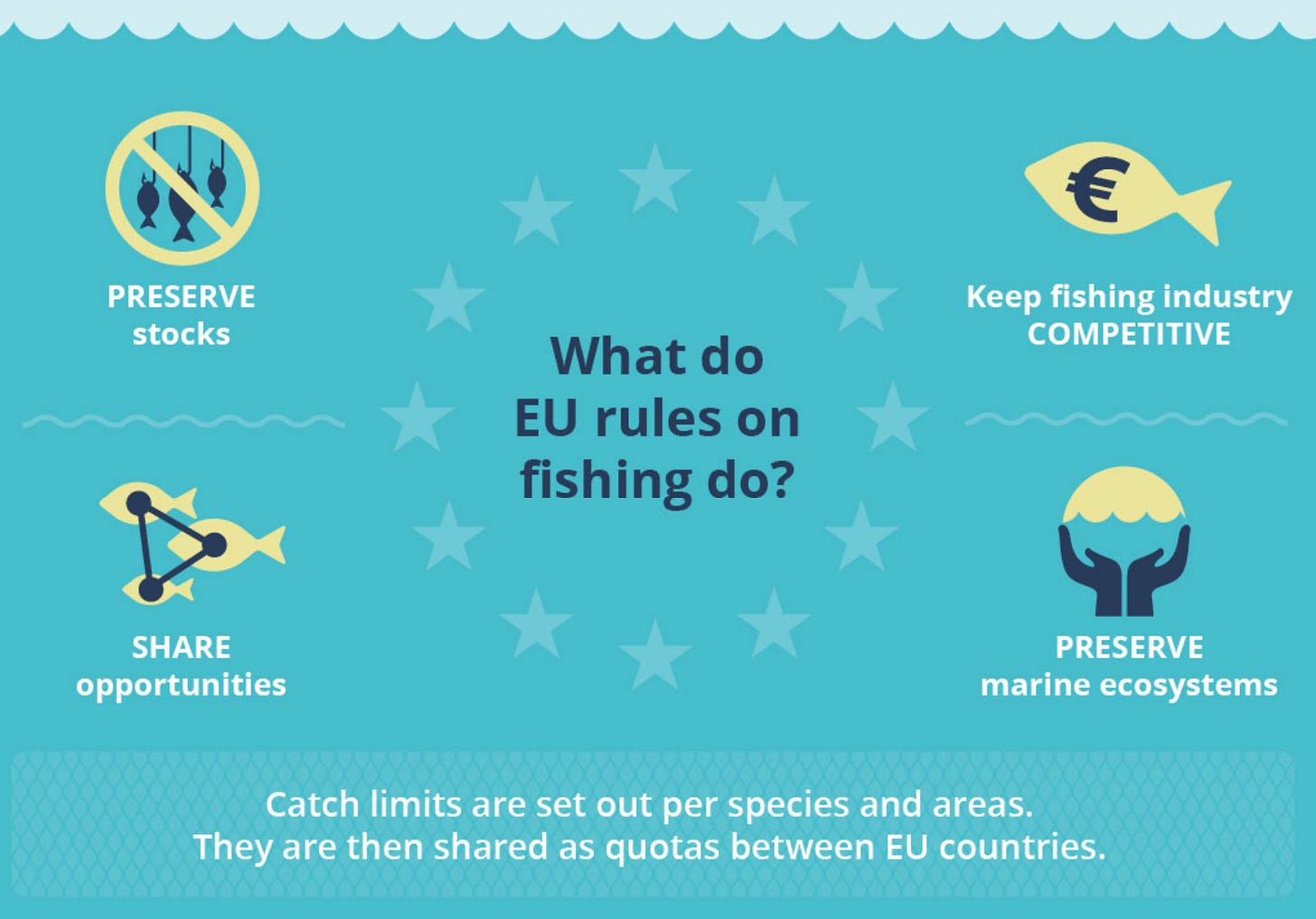

To further illustrate this point in a Baltic context, we may study the pedagogic infographic where the European Council illustrates the logic of fish quotas. The headline speaks volumes, literally: “Keeping the seas stocked”. Four symbols illustrate what EU rules on fishing do: (i) preserve stocks, (ii) share opportunities, (iii) keep the fishing industry competitive and, lastly, (iv) preserve marine ecosystems. We want a lot of fish that we can share between humans in a way that makes the EU win a competition with other states. Virginijus Sinkevičius, EU Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries, further explains the last goal of preserving marine ecosystems: “The Baltic Sea is not in good shape. It’s time to save this sea for the people who live around it, for our fishers and for future generations”. The message from both policy and communication is clear: the sea needs saving for the sake of humans. With this perspective, we will fail. “Keeping the seas stocked” is an impossible idea!

To transform into a culture capable of living in peace with nature, we have to correct this misunderstanding in how the world is structured. In the words of Thomas Berry, “we must say of the universe that it is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects”. This is what the movement for rights of nature is doing. One of the key issues for rights of nature is representation: who will speak for nature? A small group of people has spent a year developing that perspective in the Nordic context by investigating the idea of an Embassy of the Baltic Sea. According to our understanding so far, the Embassy will be a laboratory of care, where we will develop our caring capacities as humans with the aim to represent the beings of the Baltic Sea where decisions influencing their wellbeing are taken.

This is all for now - I will definitely get back on the Embassy later. In the meantime:

follow @balticembassy on instagram,

read a newly published article in Nordic Environmental Law journal: “Moral imagination for the rights of nature: an Embassy of the Baltic Sea”

see a presentation of the Embassy of the Baltic Sea (in swedish)

for a legal perspective, see a recent seminar at the Royal Academy of Sciences: How can Law inspire hope for an inclusive Anthropocene?

Find more european water bodies with human voices at the Confluence of European Waterbodies

*For context: I was part of lobbying the Kunming-Montreal biodiversity framework towards COP15 two years ago, to include rights of nature. The agreement contains the wording: “The Framework recognizes and considers these diverse value systems and concepts, including, for those countries that recognize them, rights of nature and rights of Mother Earth, as being an integral part of its successful implementation” (C 7 (b)). This is the first time rights of nature are part of international policy. Earth Law Center took lead on this work and developed a report for COP16: Ecocentrism in the Global Biodiversity Framework, outlining how countries can harmonize their legal systems with the laws of Nature under the framework of “Mother Earth centric actions” and how in particular the “least developed” countries and small island states, can secure portions of the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund intended to reach $200 billion per year by 2030.